THE BUSINESS OF BLASPHEMY

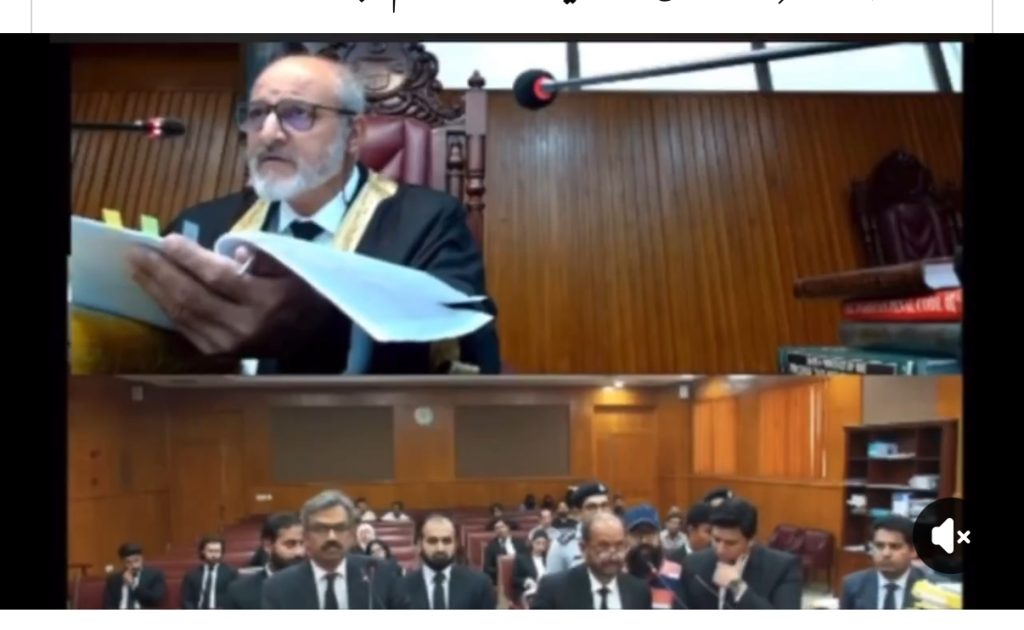

In a courtroom in Islamabad, the kind of truth that rarely survives in this country is finally clawing its way to the surface. It’s not polished, it’s not palatable, and it’s certainly not easy to witness. But it is real. So real that the court itself decided the only way forward was to let the nation watch. The proceedings were ordered to be live-streamed, a move so rare and so radical in Pakistan that it almost felt like the judge had torn down the walls and invited the country to bear witness to its own moral decay.

This is not a typical blasphemy case. It is a story so grotesque that calling it “blasphemy” feels dishonest. This isn’t about offense to religion. This is about how religion has been made into bait. This is about how something sacred has been turned into a trap—digital, deliberate, and deadly. The petition before the Islamabad High Court asks for something simple, yet monumental: the formation of a judicial commission to investigate a criminal racket that allegedly uses Pakistan’s blasphemy laws as a tool for extortion, blackmail, and personal vendettas. The syndicate, as laid out in the petition, would fabricate chats, selectively crop screenshots, weaponize emojis, and then accuse men of blasphemy based on manipulated online interactions. Some of these interactions were flirtatious in nature, others seemingly mundane. But once the trap was sprung, it didn’t matter. The FIRs were filed, and the victims were either arrested, silenced, or vanished.

The accused mastermind of this racket, a young woman named Komal Ismail—known to some as “Imaan”—has refused to appear in court. Repeatedly. So the judge did something extraordinary. He ordered her national identity card to be blocked. He demanded answers from the Federal Investigation Agency’s cybercrime wing. He asked questions others were too afraid to even whisper. Why had this case been ignored? Why were the accused not arrested? Why had the system looked away for so long?

Presiding over all this is Justice Sardar Ijaz Ishaq Khan. Not a judge with a flair for the dramatic. Not a man intoxicated by the limelight. But someone who, in a courtroom where blasphemy is usually screamed, dared to ask questions in a whisper. There’s a quiet courage in his presence. It’s not performative. It doesn’t need to be. Because in a country where even a false accusation of blasphemy can get you lynched, simply insisting on due process is itself an act of rebellion.

And then there’s the man sitting across the aisle—Advocate Rao Abdul Rahim. His name is not unfamiliar to anyone who’s followed Pakistan’s legal misuse of religion. He has built his career around the defense and expansion of Pakistan’s blasphemy laws. He has filed petitions against films, journalists, books, websites—anyone or anything he deemed a threat to religious purity. He has done so with a tone of divine certainty, as though the courtroom were his personal pulpit and justice itself was a matter of religious conquest.

Now, in a twist so bitter it stings, Rao is defending the very people accused of manipulating blasphemy for financial gain. He represents parties connected to Komal Ismail. He walked into the court as though nothing had changed, as if he hadn’t spent years helping to forge the very laws that are now being exposed as weapons. During one hearing, he objected to the judge’s remarks about his absence and claimed he hadn’t been given the chance to present his case. Justice Ijaz reminded him—calmly, but firmly—that this is a daily hearing, broadcast live, and that he has had every opportunity to show up.

What plays out in that courtroom is more than a legal proceeding. It is a symbolic war between two realities. One in which the law is sacred and protects the innocent. The other, far more familiar, in which the law is a bludgeon, passed from hand to hand by men who claim to speak for God. Rao Abdul Rahim is not just a defense lawyer in this case. He is the embodiment of everything that has gone wrong. He represents the state’s long-standing willingness to hand over morality to mobs and allow law to be dictated by loudness, not justice. And Justice Ijaz, by contrast, represents a flickering, endangered hope that not all is lost—that someone somewhere in the system still believes in accountability without vengeance, in truth without terror.

The accused, by most accounts, didn’t just exploit loopholes. They weaponized trust. They used religious vocabulary as a costume. They knew exactly what they were doing—fabricating sins and feeding them to a society addicted to outrage. And when their victims tried to defend themselves, they were told not to. Because in Pakistan, even denying blasphemy is dangerous. Once the accusation is made, you’re already half-condemned. It doesn’t matter who you are. The noose tightens before facts arrive.

What makes this case even more grotesque is how little public attention it has received. Where are the journalists who foam at the mouth for headlines? Where are the news anchors who weep on camera for the sanctity of faith? They are silent now. Not because they don’t know—but because they do. Because the truth in this case doesn’t flatter their version of righteousness. Because the truth in this case says something no one wants to admit: that the biggest danger to religion is not the people who question it, but the people who monetize it.

If you want to see what we’ve become as a nation, don’t look at our parliaments or our military parades. Look at this courtroom. Watch the livestream. Hear the silence of the victims and the confidence of their accusers. Watch a country try, once more, to pretend its soul hasn’t been sold. And ask yourself: when religion becomes a trap, and law becomes a cage—who will speak?

Because right now, in Islamabad, one judge is trying.

And the rest of us are watching.

Let them try to silence this truth. Let them accuse, divert, distract. But know this: no matter what happens in that courtroom, we now know. We know the business of blasphemy is real. We know who profits from it. We know who defends it. And we know who dares to question it.

And maybe, just maybe, that knowledge will be enough to keep the next victim alive.

متعلقہ

ایمان مزاری نہیں مزار ہے یعنی گورننس کی قبر ہے، طاہر احمد بھٹی

غزل ، از ، مدبر آسان قائل، جرمنی

What are Ahmadis in Pakistan, legally? By; Mona Farooq